Part A Introduction and Akbari hunting images

Hunting Scenes Under Jahangir’s Reign

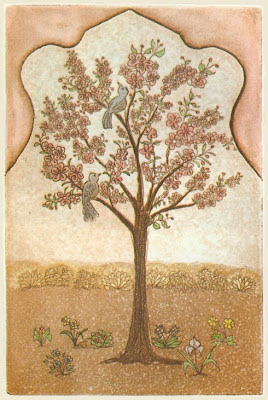

Unlike his father, Jahangir’s commissions of hunting scenes did not concentrate on actions and movement. Instead, human personalities and individuality are emphasized. Jahangir inherited Akbar’s royal library and workshop, and dismissed a number of painters. His atelier was smaller than that of his father due to his higher standards. To Jahangir, his passion for the observation of the nature affected his artistic taste. His interest in animals and plants was shown in the paintings of his period. He observed the beauty of flowers and the precious birds he saw in Kashmir. He ordered the artists to paint pictures of them. He is considered as the connoisseur among the Mughal rulers. One single artist with greater responsibility in the workshop determined the final appearance of a painting, which made artist’s individuality shown in the painting more possible. Like his predecessors, Jahangir was eager to claim his Timurid heritage. The inscription on a monumental column he erected in 1605 tells Jahangir’s lineage down to Timur. Though during Jahangir’s reign, the empire was stable, the Mughal legitimacy was still needed to be established. Linking his rule to Timurid tradition underlines his divine kingship and undoubted power.

Jahangir is an emperor with a complex personality. He was a keen naturalist, who studied animals and precious birds when he was traveling in his kingdom. Two cranes were taken to his court at the age of one month, and given the names of Layla and Majnun who are the tragic lovers of Persian literature. Jahangir devoted himself studying the cranes from their daily routine, mating, to the hatching of the eggs, and all details were carefully recorded. On the other side, he loved killing animals. In 1617, he listed 28,532 animals killed by him at the age of fifty, including mountain goat, sheep and deer, wolves, wild fox and boar, pigeons, hawks, pelicans, a total of 86 lions, 3473 crows and 10 crocodiles.[18]

Continue reading “Mughal Series|An Examination of Mughal Hunting Scenes (Part B Jahangir and Shah Jahan)” →